November 7, 2025

By Lauren Du Graf

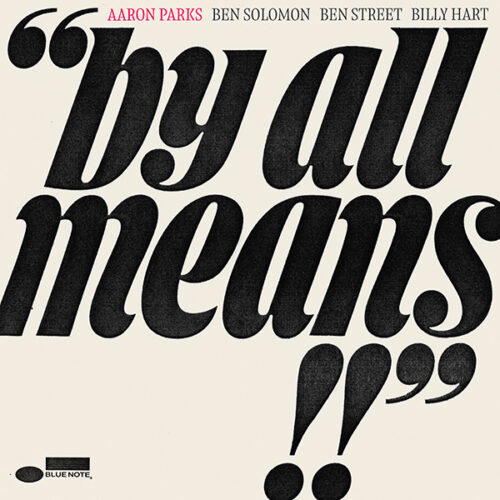

In the spring of 2023, while on tour in Portugal, Aaron Parks had a dream. It concerned an upcoming week of shows at the Village Vanguard, where he was scheduled that July to play alongside the bassist Ben Street and drummer Billy Hart. The trio had been intermittently active since 2012, although the bonds between them ran far deeper than a decade of occasional gigs might suggest.

That morning, Parks awoke to a vivid feeling: he should add a saxophonist to the mix, expanding the group to a quartet. Bringing in a horn player would broaden the color palette and give Parks more space to explore another dimension of the conversation he’d been building over the years with Street and Hart. He could give himself over more fully to the rhythm of the rhythm section, serving the song not as its primary center of attention—as the piano often is experienced in the classic trio format—but rather as one of the hosts, comping for another soloist, focused on making the thing feel good from the inside out.

You’ll hear what he had in mind on “Anywhere Together,” a jostling, rambunctious swinger he wrote as a teenager. It’s there, too, in the warm, embracing contours of “Dense Phantasy.” The whole record pulses with a kind of relational time that’s too alive for a grid—a supportive, elastic way of moving together. Even in the ethereal space of the rubato opener, “A Way,” there’s an undercurrent of propulsion, shaped by Street and Hart’s supple, deeply attuned playing. The time bends, but dances.

By All Means is a record that Parks decided to make on the fly. It’s the fruit of a dream, and as such is a submission to the wisdom of the unconscious self. Yet it’s also the harvest of decades of friendships and artistic investment, as well as Parks’s slow and meticulous (obsessive even) compositional process, with many details weighed, tested, and revised over the years. The result is both luminous and surreal, constructed with the care of a jeweler setting a diamond, yet receptive to the direction of a light breeze.

The magic between Parks, Hart, and Street is nothing new; one version of it can be found on their exquisite ECM record Find the Way (2017). Hart and Street’s friendship dates back to the mid-1990s, while their musical connection was honed over the subsequent decades in bands including Hart’s own quartet. Street can trace his fascination with Hart to his childhood in Maine; he was around four years old when he first heard the sound of his drums on records by Stan Getz, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis and Shirley Horn. His feeling for the drummer would develop into an understanding so subtle and thorough that Hart said it “forces a condition of total trust.”

Street, in turn, exerted a singular influence on Parks, becoming an older brother figure when the pianist first moved to New York. Late-night listening sessions at Street’s apartment gave way to long conversations and debates “about music, art, philosophy, all of it,” said Parks. “He introduced me to so much music that changed me, and he challenged me to stop trying to be what I thought other people wanted me to be.” A co-producer on the project, Street anchors the album with a potent blend of “empathy, wiles, and gnarl,” according to Parks. “He’s the lynchpin of the whole thing.”

The morning after the dream, the saxophonist whose name came to mind was 31-year-old Ben Solomon, a Chicago native whose playing had caught Parks’s ear the year before. A mentee of Wallace Roney steeped in the language of John Coltrane and the Impressionism of Ravel and Debussy, Solomon brought an irrepressible edge to the group, sharpening Parks’s unusual melodic lines and uncanny harmonic inventions with grit and erudition.

To Solomon, the call to work with the veteran trio presented both a thrilling surprise and an intense challenge. He likened the hidden harmonic complexity of Parks’s compositions to Wayne Shorter. “The melody will be very simple, like something a kid could sing,” said Solomon. “But the depth of the harmony underneath contains a really unusual mixture of colors that brings something out of the melody with a unique emotional character that stays with me.”

That July, Hart was playing at the top of his game, in the midst of a marathon three-week run at the club (including a week with his own quartet). Night after night, the drummer made careful adjustments to his drum parts for Parks’s compositions until he found the angles that felt right. Street was astonished by the depth of Hart’s investments in the pianist’s music. “You don’t get a master genuinely responding from the heart to a young person’s music so much.”

For Hart’s part, the equation was simple: “If you do something I like, I’m going to respond,” he said. “It’s fun like that. You’ll be able to tell that I like it.” Hart marveled at Parks’s capacity for emotional perception, comparing him to his greatest mentor, Shirley Horn. “It’s something deeper inside of me that is familiar with what Aaron is playing. It’s something like I’ve heard before, rather like in a movie or in a dream or something.”

The chemistry of the quartet that week was so compelling that in the middle of the run, Parks decided to try and capture it. A last-minute live recording session at the Vanguard wasn’t possible, so Parks secured a two-day window at Andy Taub’s Brooklyn Recording studio in Cobble Hill, just five miles south of the club. The catch was that in order to make the scheduling work, Billy would have to come into the studio before he went to the Vanguard later that evening for his own gig. No small feat for any person, let alone a man in his eighties. “I don’t know how he did it,” said Aaron. “We recorded for five or six hours each day, then he went into the city, played two full 75-minute sets, and got up and did it again.”

Aaron’s compositions on By All Means are dense with ideas, melodies that lodge themselves in your brain for weeks, and harmonic turns that aim at the heart while sidestepping the usual sentimental routines. There are songs for his family: a gentle, searching dance for his wife (“For María José”), a restless lullaby in three for his son Lucas (“Little River”), and one for himself, “Parks Lope,” an off-kilter medium swing loaded with curious turns whose title embeds a bit of a dad joke as well a reference to his distinctively uneven gait.

It is an album which draws upon many, if not all, of Aaron’s available means. Which, to speak of him alone, are downright excessive. He is an artist of profound intellect and technical facility, intensely engaged, emotionally curious to a degree that verges on a liability.

And yet, following the birth of his first son in 2020, Parks’s life had become less about his own gifts and predilections than ever before. In a sense, By All Means can be taken as the pursuit of creative openings furnished by the expansive demands of fatherhood, particularly the need to let go of what cannot be controlled, to surrender to a story larger than your own.

Becoming a parent can force a deep reckoning with who you are at the core. The everyday grind of raising children strips away artifice, bringing you back to what’s essential. There is a parallel journey of return in this album, whether to past compositions, or to a natural feeling that comes out when Parks is making music with people he’s in tune with. The music is emotionally direct, unabashedly swinging, and familiar—in multiple senses of the word.

The track I find myself coming back to the most is the album’s final offering, “Raincoat.” Its curious magic is understated, revolving around a humble ostinato and a wayward melody. Parks, Street, Hart, and Solomon, each from a different generation, offer their own gentle yet defining crosscurrents, with Hart encoding the song with a groove that is timeless, wise and hip at the same time. There is no clever new concept to be found here. It sounds like coming home.