September 16, 2014

“Fats Waller is a special kind of provocateur. It stems mainly from the fact that he was a singer as well as a pianist. Sometimes he was like an MC. It has always amazed me that a pianist whose playing was so deep could sing and keep a running commentary of what was going on around him all at the same time.”

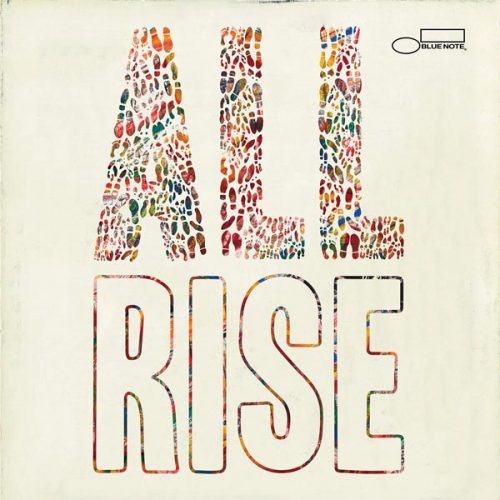

Jason Moran‘s description of Thomas Wright “Fats” Waller (1904-1943), the legendary Harlem jazz master, helps explain the spirit of collaboration and ebullience that pervades All Rise: An Elegy for Fats Waller, Moran’s ninth album for Blue Note. The fruit of a partnership between Moran and singer-songwriter Meshell Ndegeocello, ten of the album’s 12 tracks are versions of the timeless pieces that made Waller one of the most sought-after jazz entertainers of the Great Depression, a key purveyor of the highly syncopated and influential style known as “Harlem stride piano”. Ndegeocello is one of three vocalists on All Rise; her trademark ruminative vocal delivery refashions the lyrics of once-jaunty Waller classics like “Ain’t Misbehavin”, “The Joint Is Jumpin’” and the early blues perennial “Ain’t Nobody’s Business”. Together, Moran and Ndegeocello pilot a groove-wise expanded ensemble (Charles Haynes, drummer to pop stars Kanye West and Lady Gaga, is in the rhythm chair for much of the album) that re-imagines Waller’s music for the 21st century.

All Rise is the studio culmination of a project that was born onstage. In 2011—nearly a year after Moran had been named a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur “genius” fellow and around the time he began an association with the Kennedy Center in Washington DC where he is now the Artistic Director for Jazz—the NYC performing arts venue Harlem Stage Gatehouse commissioned Moran, a longtime resident of Upper Manhattan, to create a tribute to Waller as part of its “Harlem Jazz Shrines” series. “My wife Alicia had the idea that it should be a dance party, and I decided to jump at the task,” says the Houston, Texas-reared pianist. “If you think about Fats, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines—all of them were making the popular sounds of their era: dance music. Unlike today, where jazz audiences generally remain seated, dancing was expected when Fats showed up to a gig. He played rent parties. He played joints, which we know from the song, were always jumpin’.”

Ndegeocello’s presence guaranteed that All Rise—and by extension, Waller’s kinetic swing—would be infused with the contemporary kineticism of R&B and hip-hop. “Upon getting the commission,” Moran explains, “my feeling was that, ‘Yes, my band could play Fats’ music fairly straightforward if we wanted to,’ but since the objective was to construct an evening-length performance in a space that lent itself to dancing, I asked myself what could be the extra layer, or the extra couple of layers, we might add to Fats’ music to provide a number of different ways for audiences to enjoy it? That’s when I reached out to Meshell. I wanted someone who could not only sing Fats’ lyrics, but be free with them, and also a musician more accustomed than I am to dealing with a crowd that’s on its feet. She was my only choice.” (In performance Moran also dons a larger-than-life papier-mâché mask of Waller’s head created for him by the Haitian artist Didier Civil)

Three years in the making, All Rise seamlessly blends Ndegeocello’s charismatic energy (she co-produced the album with Blue Note president Don Was) with the keyboard mastery and creative ideas that Moran has demonstrated over the course of his tenure at Blue Note. “I suggested the drummer, Charles Haynes,” Ndegeocello remembers, “because he has facility and his pocket is one you cannot hear and stand still. The dance aspect of what Jason proposed really excited me. He already had arrangements and visions of how it would feel, so I just tried to add the speaking and singing aspect of the performance.”

Moran credits Ndegeocello with another component: recruiting award-winning engineer Bob Power, the mixer known for honing the sound on classic records by hip hop acts A Tribe Called Quest, Common and The Roots. “Bob’s a legend who’s worked with Meshell a lot,” says Moran, “and he brought subtle things to the sound of, for example, ‘Handful of Keys’, the one piece I perform solo piano, that really enhanced it in ways that got beyond the just-roll-the-tapes-and-play realism that is standard jazz practice.”

Moran’s theory about what makes Waller’s music a great vehicle for a millennial update is also telling. “To some extent, any musician riffing could be said to be live sampling,” he opines. “Think about it a second: If someone is playing a riff behind a solo in a big band, they’re ostensibly setting up a bed of repetition for the music to float on. It’s similar to a sample. In that respect, Fats Waller’s playing had done much of the work for us already. My role was to look for what parts of his stride, his groove, to extract and place on other grooves.”

As an example, the pianist cites the arrangement of “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” one of the album’s horn-centered tracks in which Moran plays Fender Rhodes. “There was this one recording where at the end Fats sings the phrase, ‘For you, FOR you, for YOU’ over and over,” Moran recalls. “It was so soulful that it stuck with me, and that bit is the basis of our groove, with Meshell repeating it, me emphasizing it on keys and the horns [trumpeter Leron Thomas and trombonist Josh Roseman] moving around it.” Meanwhile, the Latin-tinged “Yacht Club Swing” is an accelerated shuffle that pairs the rhythm section with muted horns and Moran overdubbing psychedelic keyboards effects reminiscent of electric Miles Davis.

Two tracks feature The Bandwagon, Moran’s long-running trio with bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet Waits. “Lulu’s Back In Town”, a stride vehicle also beloved by Moran idol Thelonious Monk, is a boppish shuffle in which the leader’s piano becomes a channel for stride as well as the stop-time expressionism of Moran’s onetime teacher Jaki Byard. Waller’s recordings of the Tin Pan Alley hit “The Sheik of Araby” were done with horns, but Moran’s interpretation keeps it strictly trio; Mateen and Waits affect a funky, oom-pah-laden stroll before everyone accelerates into the gallop that turns the piece into a medley with another Waller favorite, “I Found A New Baby.”

Moran explores Waller’s romantic side in two other vocal features, the Hoagy Carmichael ballad “Two Sleepy People” and the cover of the icon’s enduring standard “Honeysuckle Rose”. Trumpeter Leron Thomas sings “Two Sleepy People” with a touch of contentment rather than Wallerian humor as Moran backs him on organ. The synth-drenched horn break in the middle of the piece is among the album’s breeziest grooves, though its subtleties owe as much to the beat-wise concepts of late mixmaster J Dilla as the animated piano-driven swing crafted for “Honeysuckle Rose”, which features vocalist Lisa E. Harris. “Lisa sings backup on the rest of the album, but she and Meshell switched places on ‘Honeysuckle’,” says Moran. “Meshell asked me to create a mental image for the song that knocked me out. She said she wanted it to be the sound of ‘Black folks sipping chardonnay in the summertime’,” he says laughing. “When she heard Lisa messing around with it one time during a rehearsal she felt instantly that was the way to go.”

The album moves furthest from the familiar on the astonishing versions of “Ain’t Nobody’s Business” and “Jitterbug Waltz”. Both are slow jams with Ndegeocello’s voice adding an extra air of introspection to her arrangement of the much-covered “Ain’t Nobody’s Business,” a tune that the famously hedonistic Waller first recorded in 1922. “Even with familiar material, the objective is to make things as personal as you can,” says Moran. “’Nobody’s Business’ is an example of Meshell completely recasting that set of lyrics. It’s like it might have been lifted off her album Bitter. The words are redistributed to add weight in different places than we’re used to hearing.”

“Jitterbug Waltz” is an instrumental that slims the band down to a quartet featuring saxophonist Steve Lehman. The arrangement hides Waller’s familiar cascading figure within a hymn. “I’ve always liked playing the piece, even going back to high school,” Moran says. “I wanted to have a different kind of dialogue with it, though. The best way I can explain it is sort of like that extraterrestrial feeling you get from hearing the Fats Waller organ music in that David Lynch movie Eraserhead. I discovered that when Wayne Shorter suggested I watch it. That’s a wild movie for real, but I liked that it sort of enables a conversation about Fats that’s not so precise and historic.”

It’s not lost on Moran that an air of the tragic surrounds Waller’s premature death from pneumonia in 1943. “Both Meshell and I were aware in titling the album that we were flirting with both uplift and mourning,“ he explains. “Fats was just 39 when he passed away. A son of a preacher with big appetites—alcohol, you name it. At the time, his work was being heard and getting recognized, which is every musician’s dream, but then suddenly he was just gone. I’m 39 now.”