February 17, 2022

Sooner or later, every jazz musician arrives at a moment of reckoning with the blues. It’s a foundational language of improvisation, and a starting point; if you live on jazz time, it’s almost impossible to escape. And despite its structural simplicity, even veterans find the blues an endless challenge – perhaps because to communicate successfully in the blues, the musician has to put aside whatever he’s learned and become involved on an emotional level. Inflections and grace notes matter. It’s futile to simply rattle off licks, because many of those squibby little flatted-third motifs have been used and recycled for a century. The only way to be persuasive within the blues is to fully engage it – as musical structure and philosophical orientation, a way of seeing and being in the world.

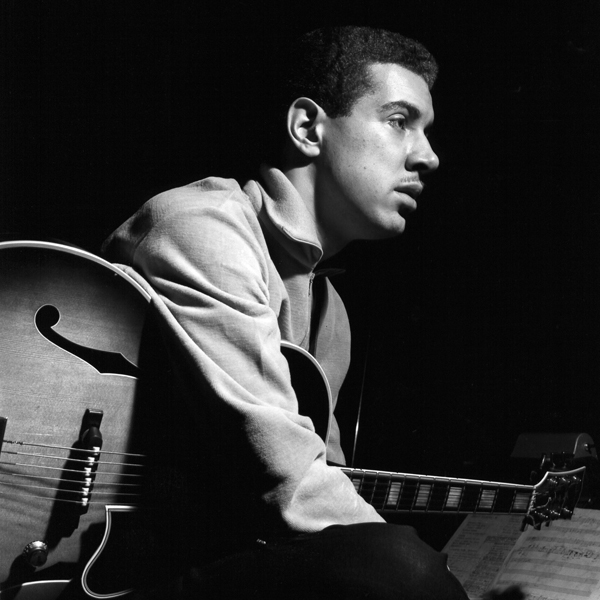

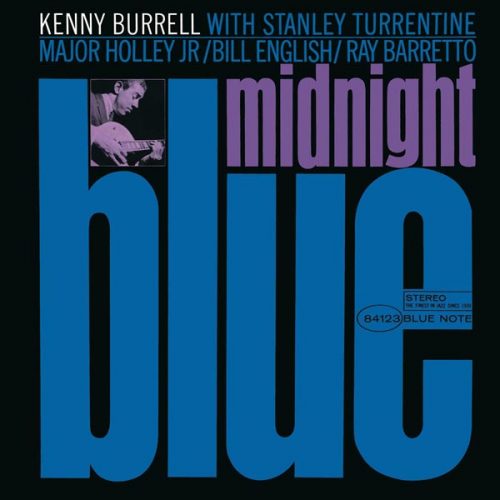

For decades, musicians seeking to develop a personal approach to the blues have turned to, and devoured, Kenny Burrell’s understated Midnight Blue. It’s a potent dose of blues feeling served neat. It’s a core text of blues-based improvisation that offers parallel wisdom about life, much of it contained within the phrase “don’t try too hard.” There’s a lesson in every chorus, not because Burrell shreds but because he doesn’t: The guitarist whose tone entranced Jimi Hendrix – and whose style was emulated by Stevie Ray Vaughan, among many others – moves deliberately, patiently, seeking fleeting illumination between the big pronouncements. The lure for Burrell here is the midnight part: He’s acquainted with the romance of the later hours, and he’s not trying to hurry them along. He lets his ideas hang in the air, smoldering like a neglected cigarette. His tunes move at leisurely last-set tempos – the molasses-slow “Mule” begins with a few stoptime choruses that showcase the supremely inviting roundness of his guitar tone – and when he does lean back to uncork some blistering run, it is usually a knockout blow, delivered with lethal precision.

Midnight Blue is one of those records that seems to live inside a stylized, high-resolution movie scene. Check out the percussive crawl that begins “Chitlins Con Carne” – it pulls listeners into the convivial ambience of an afterhours bar where possibly shady dealings are going down, and the band is only thing keeping the peace. After a few tunes that conjure different perspectives on that same scene, Burrell gives the band a breather to play, alone, his gorgeously dejected “Soul Lament.” Here, he shows how blues mastery goes beyond notes, to include shading and pitch-bending and all sorts of sonic manipulations as the tone decays. Hear him attack a note on this riveting meditation, and you don’t stop to wonder if he “means” it: You know. His phrases arrive electrified with conviction, and a bit of wily warrior energy. The program ends with a deceptively intense medium swing entitled “Saturday Night Blues,” and here Burrell shows an entirely different facet of his art: Listen to the way he plays behind tenorman Stanley Turrentine, fashioning liquid long tones and syncopated slashing chords into a gently agitated, and utterly ideal, backdrop. Turrentine never had it better.

These days in jazz, there’s a tendency to over-analyze, to put every note played by a major figure under the microscope. Some recordings defy such scrutiny. Midnight Blue is one of them: Take it apart and study it all you want, but just as with the works of the great bluesmen, if you don’t dive in fully and listen with an open heart, you’re probably going to miss some essential part of the message.