September 14, 2018

Randy DuBurke will always remember that auspicious moment when the news arrived. It was St. Nick’s Day in Switzerland, where the Brooklyn-raised illustrator resides. After DuBurke had finished making holiday magic for his kids, an email brought an enchanted possibility for him: Wayne Shorter admired his books, and wanted to collaborate on a graphic novel and recording project.

“I said, ‘The Wayne Shorter?’” DuBurke says. “I was sitting in my studio looking at my CD collection, and my eyes lit on ‘Speak No Evil’ and ‘Beyond the Sound Barrier.’ At that point I knew I had to be a part of this!”

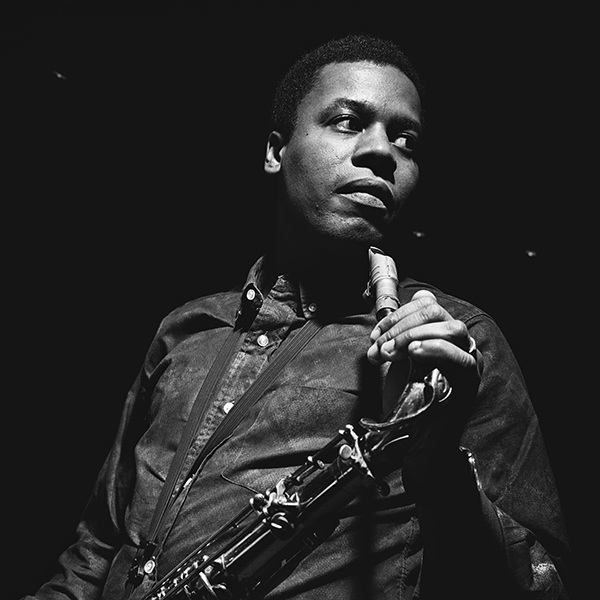

At the suggestion of Blue Note president Don Was, Shorter had checked out DuBurke’s well-respected illustrations in graphic novels on Malcolm X and Deadwood Dick. “I could sort of project myself into Randy’s general state of mind from childhood,” Shorter says. “I could see it in his drawings. He has those ‘I wish’ lines in his work; he’s aiming for how he wants the world to be.” Shorter is a serious comic book aficionado, and has long identified with the genre’s heroes and alternate realms—he even created his own comic book of blue ink drawings, Other Worlds, at age 15.

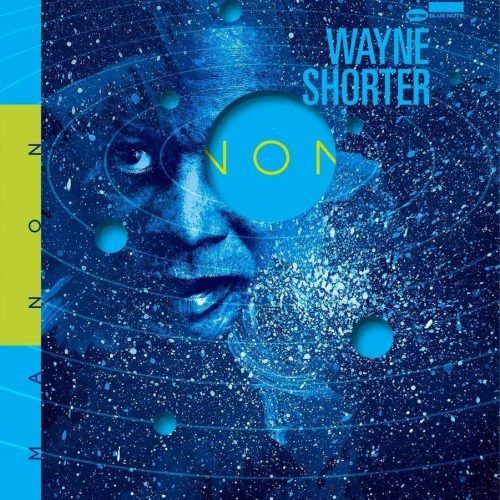

To launch his collaboration with DuBurke, Shorter had four studio tracks: “Pegasus,” “Lotus,” “The Three Marias,” and “Prometheus Unbound.” Shorter’s long-running quartet with pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci, and drummer Brian Blade recorded this music with the 34-piece Orpheus Chamber Orchestra in February 2013, the day after a combined Carnegie Hall performance.

“Just before Miles passed,” Shorter remembers, “He said, ‘Wayne, I want you to write something for me with strings and an orchestra, but make sure you put a window in so I can get out of there.’ He definitely did not say, ‘Make the strings swing.’ Working with an orchestra is like crossing the street and talking to a neighbor you haven’t talked to for 10 years. It’s the thing the world needs now: joining forces.”

Shorter says the agile Orpheus orchestra, which is conducted cooperatively by the musicians themselves, caught the vision and spirit of his wide-ranging music. “The feeling was, ‘Where do we go from here? Straight up!’ That’s the excitement the orchestra musicians exuded in the studio. Everybody had a voice. We’d stop here or there, somewhere in the middle, and one of the musicians would say, “Hey, do you think this line should be more vocal? Yeah, let’s try it that way.’ Everyone was on their toes, and it was a labor of love.”

The title of this four-composition orchestral suite is also Shorter’s title character for the graphic novel: Emanon, or “no name” spelled backward. “When Dizzy Gillespie had a piece of music in the late 40s called ‘Emanon,’ it hit me way back then as a teenager: ‘No name’ means a whole lot.” It meant something that the Dizzy Gillespie/Milton Shaw tune, arranged by John Lewis in 1946, transcended big band jazz conventions with a more modernist statement. Innovation, authenticity, and self-reliance were hallmark virtues of the midcentury art and culture that captured Shorter’s imagination and shaped his artistic character.

“The connection with Emanon and artists and other heroes is the quest to find originality, which is probably the closest thing you can get to creation,” Shorter says. “Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and some comic heroes, they lose their power or identity and become something called human, so that a human being has to do the same thing that Superman and all of them do.”

After DuBurke had a long talk with Shorter about the composition titles, quantum mechanics, and much else, he got to work. “I’d put the Emanon cuts on,” DuBurke says. “Or I’d watch Cosmos videos with Neil de Grasse Tyson. Whatever came into my head as I sat at the drawing board, I sketched in black and white or in color. Wayne said, ‘Nobody’s gonna edit you, just go with it.’ So I felt entirely free creatively, and delivered some first story sketches to Wayne.”

With DuBurke’s panels in hand, the screenwriter Monica Sly, who helped Shorter and Herbie Hancock write their viral 2016 “Letter to the Next Generation of Artists,” worked with Shorter to develop and structure the graphic novel. Central to the story was the multiverse theory, or the idea that the universe we inhabit is one of an infinite number that all exist in parallel realities. Listening to each of four orchestral tracks, Sly and Shorter “came up with a fear that matched the vibe of the track,” Sly says. “That ‘fear’ then defined the world Emanon would be inhabiting in that specific universe of the story. And each of the four universes exists simultaneously—from what I know, that’s very in line with the improvisational, everything-exists-in-the-moment aspect of jazz.”

The lead track and first Emanon world, “Pegasus,” addresses the complacency of people who fear their power and potential, instead living within prescribed boxes. Shorter certainly composes well out of the jazz box on “Pegasus,” with a style as much in the lineage of great American composers like Copland, Gershwin and Ives as the one of Ellington and Monk. Characteristically, the composition’s advanced harmonies defy conventions while its soulful lyricism affords accessibility.

Early in the collaboration, Shorter mentioned a Pegasus cover illustration for a science fiction book by Anne McCaffrey. But listening to the composition, DuBurke didn’t see the ubiquitous white winged horse of Greek mythology; he envisioned the earlier Pegasus of Ethiopian myth, a brown horned and winged creature. When DuBurke gave Shorter a few working Pegasus sketches at a concert in France, creative inspiration flowed back to the source: Wayne kept DuBurke’s illustrations on his music stand as he performed, using them as an improvisational muse.

The “Lotus” track and universe speaks to the destructive effects of divisive thinking, and how a fear of difference can lead to war. For Shorter, the Buddhist symbol of the lotus flower presents an alterative. “The lotus exists only in the swamp, in our world of turmoil, and the blooming flower purifies the water around it. Within the story, those workings of the lotus are being carried out through Emanon’s actions.” Within the music, the quartet’s energetic cadenzas grow from the larger orchestral landscape, clarifying and enhancing its themes.

In “The Three Marias” universe of the novel, Emanon confronts the fear of knowledge that leads to censorship and the suppression of thought and free will. The real-life arrest of three Portuguese women for writing obscene literature inspired the original electric version of “The Three Marias” on Shorter’s 1985 Atlantis album. Shorter later revised the piece for performance with the woodwind quintet Imani Winds.

In a testament to the considerable symphonic expertise of his sidemen, Shorter asked Perez and Patitucci to orchestrate “The Three Marias” for the version heard here. “I think he asked us in the spirit of a father challenging his sons,” Patitucci says. “To give us a chance to do something special.” Perez and Patitucci collaborated on tour, meeting before and after shows with Wayne, passing the score back and forth. “We focused on the strings mostly,” Patitucci says. “And after we’d performed it live, we wound up honing it even more—it was fitting, because that’s Wayne’s own method, endless revision.”

Emanon’s “Prometheus Unbound,” an enthralling episodic piece of music, concentrates on the fear of the unknown, and proposes an embrace of the fluidity and unpredictability of life. That summarizes the overall development within the character Emanon, who for all the novel’s science fiction adventure elements is essentially an everyman on a universal hero’s journey. “Emanon is like so many characters in that role of trying to find a way in the world, and also make the world around him a better place,” DuBurke says. Longtime fans of Shorter may read something of the musician himself into the character. “Wayne is fearless in the face of adversity,” Sly says. “Excited by the prospect of the unknown. Brave enough to stand up for justice and stand out in a crowd, yet sensitive and aware of the value of each life around him.”

“Wayne is the great American composer,” Patitucci says. “It’s always been a matter of him having the chance to display all that he can do in large musical forms, and also in his other areas of brilliance and imagination like art and storytelling, too. So Emanon is a fulfillment of a lifetime vision.” It’s almost an embarrassment of riches that Emanon is a triple-album release, with the two-disc Live In London quartet recordings of the orchestral material, along with “Lost and Orbits Medley,” “She Moves Through The Fair,” and “Adventures Aboard The Golden Mean.”

With Emanon, Wayne Shorter shares his artistic multiverse. Everyone will create his or her own experience with the novel and music—but be prepared for that experience to involve the unknown. “After reading and listening to Emanon, you might begin to notice alternative realities glimmering beneath the everyday world around you,” Esperanza Spalding writes in her introduction.

“A sense of awe and wonder was something that Wayne and I wanted to get to with this project,” affirms DuBurke. “I would hope with Emanon that people would have some sense of the music washing over them and images pulling them in, almost a sensory overload that takes them deeper into themselves, which is also deeper into the multiverse.”

—Michelle Mercer, June 2018

Michelle Mercer is a New York Times bestselling author and a regular music commentator for National Public Radio. She is the author of Footprints: The Life and Work of Wayne Shorter and Will You Take Me As I Am: Joni Mitchell’s Blue Period.